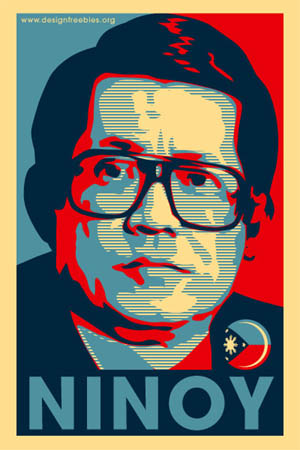

I’ve been reading a book about the assassination of Ninoy Aquino, written by former Time correspondent and long-time Philippines watcher Sandra Burton. Burton’s exceptional account in “The Impossible Dream” describes the emotional highs of Ninoy as well as his near-fatalist feelings about the potential for foul play upon landing back in the Philippines, where he’d been exiled by the Marcos camp for years: he wore white on the airplane as a sort of symbolism.

Burton was on the airplane with Aquino and heard the gunshots when he was killed point-blank as he got off the plane, likely by security forces. It remains a mystery to this day exactly who ordered the killing, but long-standing Filipino dictator Ferdinand Marcos was at the top of the list, alongside his chief of staff, General Fabian Ver.

I had just made it about halfway through the book when I heard about Sam Rainsy’s imminent return to Cambodia, and I immediately got to thinking about the parallels here.

Both Aquino and Rainsy have spent years in off-and-on exile from their native countries, thanks to their political viewpoints. Both are (or were) considered the symbolic leaders of the opposition movement against a long-standing and corrupt leader, who had made it absolutely plain that he had no intention of loosening his grip in power early. And both received a surprising eleventh-hour pardon that allowed them to return to the country to follow their political goals. Unlike Aquino, who served years in prison and conducted high-profile hunger strikes, Rainsy has taken the hint and has put himself into self-imposed exile to avoid jail-terms — probably to his political detriment.

Marcos and Hun Sen have their similarities as well. Both have paid some lip-service to the notion of democracy and “fair” elections, but are actually totally devoted to the cause of retaining power for themselves. Both Asian leaders built a large share of their reputation and their popularity among the people on the basis of growing economic stability, and in barest terms, roads.

Ferdinand Marcos and his government claimed that they “built more roads than all his predecessors combined, and more schools than any previous administration” — while Hun Sen on the campaign trail regularly points to the roads he’s built and the economic improvements that have occurred in his Cambodia as proof of his legitimacy. “Compare things with 1979, what we had at that time and what we have at this time,” Hun Sen told the Phnom Penh Post recently, invoking the possibility of an unpleasant “guardian spirit” that could attack those who failed to recognize all that he had done for them.

Indeed, Hun Sen and both Marcoses — Ferdinand and Imelda — seem to share a patriarchal, indignant attitude towards the people, most evident when they feel the polis has wronged them in some way. Imelda saw herself as the “star and slave” of the people who was obliged to dress nicely amidst the barrio for them; so too does Hun Sen seem to see himself as an avenging hero, out from the jungle to serve as the selfless samdech of the public. They are personally hurt, or sound that way when they are criticized: they act as if they have been told off by a child or a close relative, and How Could You Speak to Me That Way, With All I’ve Done For You? When All I Want is What’s Best For You?

There’s some similarities in play here. But do they extend far enough to the barest possibility of some harm being done to Sam Rainsy on his return to Cambodia? Would Hun Sen get anything out of making such a move?

It’s possible. Maybe. But I think that unlike the sickly Marcos of 1983, Hun Sen is too good a chess player to harm Sam Rainsy — at least during the election period. For Hun Sen, occasionally pardoning Rainsy then rescinding the privilege when international attention turns elsewhere has been a relatively fool-proof technique, and he hasn’t had to harm a hair on Rainsy’s head for the whole procedure to work.

He simply has to wait until Rainsy does something he can pounce upon again, and as matters stand in the summer of 2013, he gets to look rather benevolent to boot. At the moment, Rainsy is probably considerably more useful alive than dead.

I asked Cambodia watcher Donald Jameson if he thought Hun Sen would make a similar decision. “I think Hun Sen is too clever to do anything like that. Allowing Rainsy back undercuts much of the criticism he had been getting about the fairness of the election and there is very little that SR can to to alter the outcome of the vote unless something very unusual happens,” says Donald Jameson.

The death of Ninoy Aquino galvanized the opposition to the Marcos regime, and saw the ouster of the long-time president of the Philippines only a year later in the People Power Revolution.

Hun Sen, I suspect, has studied the situation and is unlikely to make the same mistake. But we will only for sure by July 20th.