When I was in my early teens I was very interested in the notion of revolution, in the abstract way of children who have been exposed to too much literature.

I was a fan of Kerouac and had been subjected to the Communist revolutions of the 20th century in my mildly cracked sixth grade class in Salt Lake City: I had read about the hippies and about Che Guevara and about the Russian revolution and the French variant on the theme as well. All these things struck me as fascinating and exotic — adventure-stories for petulant youth (and in many ways, that is what they are).

My friend Kelly gave me a book on Revolutions for my 14th birthday, which focused on the concept of revolution and considerably less on the actual reasons why one might do such a thing: this was in retrospect ideal.

Those were the days when I wanted a revolution, when a revolution sounded like a great and vague idea. I would read books about Marxism by our swimming pool on summer days back then, and read the Anarchist’s Cookbook, and quietly, abstractly seethe in the car as my parents drove it to a local gastropub. It was the early 2000s, and everything in American life was going exactly as planned. It was really pissing me off.

9/11 had happened and George W Bush had also happened, and the Iraq War too, but on the whole, America remained insulated from the nastiness of economic upheaval and poverty.

At that time, my family and myself lived in a suburban California world of organic food and reasonably nice lawns and BMWs — calm and stable and quiet, with clean air and water and the sort of crime that breaks into your house when you’re away, but doesn’t kill you. We had no Vietnam War to galvanize us then, and World War II was a distant memory. Racism and sexism were being pushed back and most people were making a reasonably adequate amount of money.

The outlook was bright, and to my mind, distressingly lifeless. The future looked calm as a glassy Swiss lake, and just about as stimulating. In such a pretty, painting-like aspect of the future, I reasoned, I’d have no chance to distinguish myself, or test myself. Homework and Getting Into College were the sum total of my world’s expected challenges, and this felt totally inadequate — not when I read the histories of people who had battle for civil rights, had slogged through World War I, had stormed the palace of the Russian czars. I wanted a revolution not because I had anything in particular to battle against, but because I thought it sounded much more exciting than doing algebra problem sets at the tutoring office.

And it would be much more exciting than algebra. At the time, I agreed with the ancient pundits who are published (eternally) in the hoariest of publication: my generation had it too easy. We had been gifted educations and an economy that generally promised good things to us if we got decent grades and behaved: it all seemed so easy, and as a kid who did not in fact get decent grades or behave (prior to a certain revelation at age 16), I was suspect of the entire principle. I was a fool. I did not know better.

And then it actually happened in 2008. Everything really did go to shit.

I remember this clearly, the moment that I realized that things had actually changed, in a way not unlike that I’d dreamed of with such innocent dimness at the age of 15 while dipping my feet in our swimming pool. It was the late and waning summer of 2008 and the cicadas were humming outside of my New Orleans apartment – I had recently returned from a long stay in India, and the sound was pleasingly exotic to me, the South encapsulated in insect-song — and I went onto my computer and saw the news.

It was bad news. Very bad. The economic implosion was upon us. A photo of George W Bush looking tired, terribly tired. Ben Bernake, looking the same. The news media wrung its hands, and the blogosphere did the same. The collapse of the economy and Life As We Knew It was prophesied, and I read for the first time (or soon thereafter) the words “too big to fail” and “great recession.”

I was twenty years old. My reaction was muted. I believe that I went to make some tea, and my thoughts had drifted to what I was going to have for dinner, before they came back to the grave matter at hand.

Could it be this bad? Was this what I wanted when I was fifteen? Can I believe it would be this bad? There is no way it could be this bad. We are untouchable.

I walked to school that morning down St Charles Avenue in New Orleans, past the oaks and the torn-up sidewalk, past streets where National Guard vehicles had rolled scant years before when the city descended into anarchy, when I was 15 years old and struck with unholy indigence at how New Orleans had been treated, how no one particularly cared.

I walked through the geography of the first major betrayal that the US had exacted upon me to my private university, and I wondered at that particularly analogy, and my confidence upon going out the door that We Are Untouchable began to falter, began a slow slide that has continued into the present day.

I got to campus and I walked, and I wondered how bad it would be. I wondered this and then I got an overpriced coffee and then I went to class and spent my day happily learning about the rise of satire in the English novel, and attending a class where we did a lot of different drawings of a box with a light shone on it.

The tuition at Tulane in 2008 was approximately $45,000 a year, and most people I knew had gone into debt to pay it — a debt they assumed would be paid off promptly enough, once they secured the jobs that were due to them as good students who had committed no major crimes. No one talked about the recession on campus on that day. It did not really come up for the next two years, until I graduated.

Perhaps we assumed — the sketchy kids who smoked outside the library, our tribe — that it was happening to other people, to people who lived in suburban homes that were painted coral and were now unspeakably underwater on their mortgages, and to men in bespoke suits, to small and pissant Eurozone nations, or whatever. New Orleans had weathered Katrina against all the odds and projections, and so would we. We’d find a way to get someone to pay us to do work that didn’t involve the tender mercies of Walmart, or working as a receptionist for someone who sold equestrian laxatives. We had talent and hard work and had been reassured for years that that was enough. We didn’t need a revolution.

I had just turned twenty years old.

It is 2014 now and I am 25 years old, and the thoughts of revolution, of wanting it, of wanting to be in it, have faded completely.

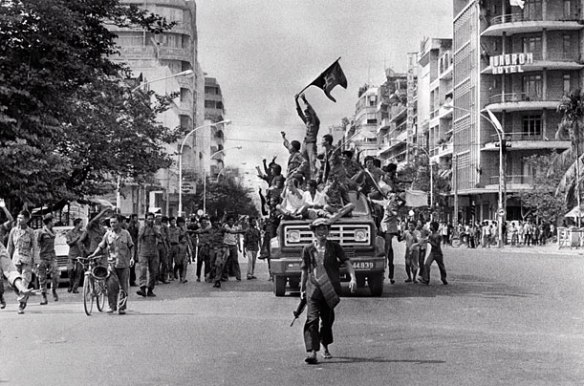

I moved to Cambodia after college and was faced with the evidence of what happens when a bunch of idealists with too much education and too little common sense decide to remake their country in their own shape: the shreds of stained and stinking clothes stored at the Tuol Sleng torture prison and the shards of bone and funeral mounds that criss-cross (terrible, beautiful) Cambodia are evidence enough of that.

I got older and learned that Che Guevara was a bombastic ass, and that Stalin caused a famine that killed millions, and the baby-boomers that had ushered in the Age of Aquarius were now frantically attempting to justify screwing my generation out of everything we had been promised scant years before.

Now, I’m scared of revolution. I have traveled in a lot of countries where revolution was a good idea at the time, now.

Revolution is the disappearing brother and the back against the wall – the dull thump of an iron farming tool against the back of the skull, the burned school and the man with no legs who sits on the corner. Revolution is a luxury resort in Bali built above the bodies of purged Communists of the 1960s, and it’s the red-resin roses painted into the cracked cement streets of Sarajevo, put there by mortar-blasts. It is journalists imprisoned in Egypt in early 2014, and it is the grey, devastated cities of a stinking, burning place they once called Syria.

The purge of revolution is intoxicating. It is alluring, especially to teenagers (like I was once) and to those who think like teenagers. It always seems like a good idea at the time. I’ll cede, perhaps, that sometimes it must be done — this purgative state, a cleansing of the humors to return to health. But it is never fun. It is best avoided.

I have lost my faith that we, in the US, are going to be able to avoid it unless something changes soon. Not just that. I’ve lost that sense that We Are Untouchable, and I have also lost that confident perception that if revolution came and upheaval took over the world, I would come out of it OK, by sheer force of will.

The suburban lawns and the regularly maintained swimming pool of Northern California are not ancient realities, now now: the villas of Phnom Penh and the dachas of imperial Russia were probably thought to be perfectly permanent by their residents at the time, too.

Even Stanford, where I attend classes, is a small holdout of obliviousness. The lawns are manicured and do not look real, and you could lose count of the number of fountains on campus that burble clear blue water, and employment recruiters wander around campus with their high-heels clicking on the slightly wobbly tiles. The students weigh multiple job offers, and talk of both social responsibility and the money they will make, of the Google or Facebook employee IDs they will sometimes flaunt at parties.

I leave Stanford often, both to report and both to clear my head. The white Google vans glide noiselessly by me on the road when I am driving to and from various points on the Peninsula. Meanwhile, the Palo Alto homeless shelters close and close, and four people froze to death during our recent cold snap. Market Street in San Francisco no longer reminds me of Christmas shopping in 2004, and the snowflakes over the Macys, but instead reminds me of the Delhi bazaar, of darker corners of Phnom Penh, where the people have been left to molder. I can buy a $13 hotdog, and I can cross over a few blocks and deign to step over a sleeping man who reeks of urine and neglect. I am on the right side of the divide, for now. I have expensive shoes. I go to Stanford. I have health insurance.

I am on the right side of the divide, and I wonder about how long I will remain on the right side.I spend a lot of time both using and reading about and thinking about Disruptive Technologies and these are their own revolution: rending capitalism in its own image, creating a large class of economically less-than-essential people, whose ranks might include my friends and my family and maybe myself.

Now, I’m afraid of revolution, but I also know there is little I can do it stop it from coming, for the oncoming wave of change and upheaval to break with a sudden, solid crash upon the shore.

In these days, I concern myself with pointing to the wave, and shouting that it’s coming, and hoping that someone will pause and listen. At the same time, I am angling crab-like uphill, hoping to secure for myself a patch of dry ground.